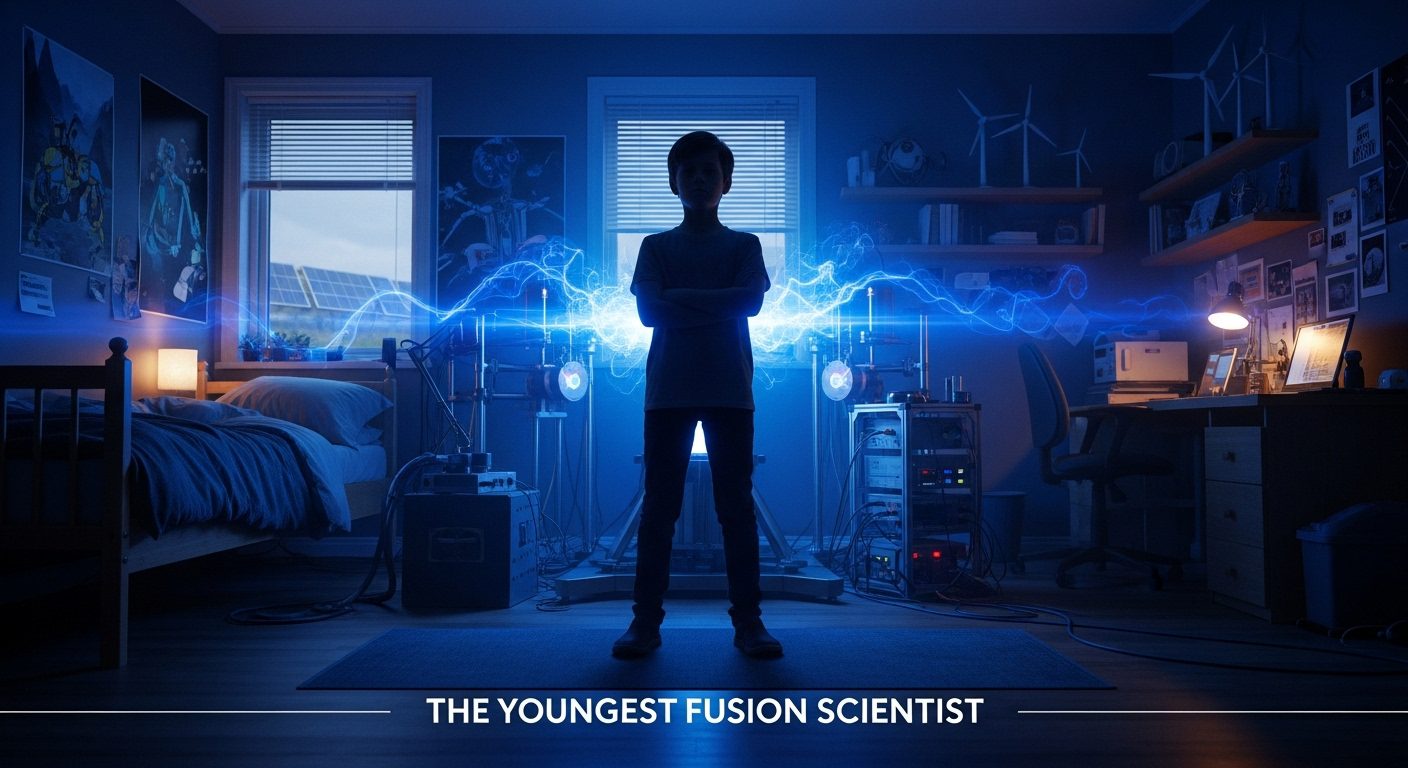

Federal agents knock on your door because they’ve detected nuclear activity. Now imagine they’re there because of your 12-year-old son’s science project.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s exactly what happened to the Oswalt family in Memphis, Tennessee, when their son Jackson became the youngest person in history to achieve nuclear fusion, the same process that powers the sun and promises unlimited clean energy for humanity.

But here’s what nobody talks about: This bedroom breakthrough might have accidentally solved one of clean energy’s biggest problems.

Jackson Oswalt didn’t set out to terrify federal authorities. He simply wanted to replicate what Taylor Wilson had done years earlier, achieve nuclear fusion before turning 14. What Jackson didn’t realize was that his obsession would lead to a breakthrough that has energy scientists rethinking everything about accessible fusion power.

On January 19, 2018, two hours before his 13th birthday, Jackson achieved something PhD scientists with million-dollar budgets often fail at. He successfully fused deuterium atoms in a homemade reactor, releasing neutrons, the telltale sign of nuclear fusion. The Geiger counter in his bedroom clicked frantically, confirming what seemed impossible: a middle schooler had just harnessed the power of the stars.

The most shocking part? He built the entire apparatus using parts from eBay, including components from liquidated research facilities. Total cost: less than $10,000. Compare that to the $25 billion being spent on the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, and you begin to understand why this story matters.

Three days after Jackson’s success, an unexpected visitor arrived. The FBI had detected unusual radiation signatures from the Oswalt home. The agent, polite but thorough, swept the house with sophisticated detection equipment.

“He was actually really cool about it,” Jackson later recalled. “He said it was just routine, making sure we were being safe.”

The visit lasted less than an hour. No radiation hazards were found, Jackson had been meticulous about safety protocols. But the incident revealed something profound: A 12-year-old had achieved nuclear fusion so successfully that federal authorities took notice.

What the FBI agent discovered wasn’t a threat. It was perhaps the most important demonstration of democratized clean energy potential in decades.

Here’s where Jackson’s story becomes revolutionary for the future of sustainable energy. Unlike previous fusion pioneers who had access to university labs and professor mentors, Jackson learned almost everything from open-source information.

His curriculum included YouTube videos from fusion enthusiasts, online forums where amateur scientists shared blueprints, and research papers freely available on the internet. He spent hours studying plasma physics, vacuum technology, and neutron detection, subjects that would challenge graduate students.

The implications are staggering. If a 12-year-old can achieve fusion using internet resources and eBay parts, what does this mean for energy access in developing nations? Could distributed fusion reactors become the solar panels of the 2030s?

While media headlines focused on the FBI visit, they missed the bigger story. Jackson’s achievement represents a fundamental shift in how we might approach clean energy generation.

Traditional fusion research follows the “bigger is better” philosophy. Projects like ITER in France require international cooperation, decades of construction, and budgets that rival small nations’ GDPs. They promise commercial fusion power by 2050, maybe.

But Jackson’s approach suggests another path: small-scale, distributed fusion reactors that could power individual buildings or neighborhoods. Imagine every high school having a fusion reactor for both education and supplementary power. Picture remote communities generating their own clean energy without massive infrastructure investments.

This isn’t fantasy. The Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory has been quietly studying small-scale fusion approaches, inspired partly by amateur achievements like Jackson’s. They’ve found that miniaturized fusion reactors, while not net energy positive yet, could serve crucial roles in medical isotope production, neutron sources for research, and eventually, localized power generation.

Jackson’s story reveals an uncomfortable truth about energy politics. The centralized control of power generation, whether fossil fuels or traditional nuclear, maintains existing economic and political structures. Distributed fusion potentially disrupts everything.

Consider this: Jackson’s reactor cost less than a used car. With improvements, similar devices could become net energy positive within a decade. Suddenly, energy independence isn’t just for nations, it’s for neighborhoods, schools, even individual homes.

This prospect challenges fundamental assumptions about energy infrastructure investment. Why spend trillions on new power plants and transmission lines when communities could generate fusion power locally? Why maintain dependence on fuel supply chains when the fuel (deuterium) can be extracted from seawater?

No wonder the FBI showed up. Not because Jackson posed a danger, but because his achievement highlighted how quickly energy paradigms could shift.

Jackson Oswalt isn’t alone. He’s part of a growing movement of young fusion enthusiasts who see nuclear fusion not as an impossible dream but as an engineering challenge waiting to be solved.

The Open Source Fusion Research Consortium now counts over 10,000 members, many of them teenagers. They share designs, troubleshoot problems, and push the boundaries of amateur fusion. Some have achieved fusion in their garages for less than $5,000.

This democratization of fusion technology parallels the early days of personal computing. What started as a hobby for enthusiasts in garages eventually revolutionized the world. Could fusion follow the same trajectory?

Universities are taking notice. MIT recently launched a program specifically for high school students interested in fusion energy. Stanford’s Linear Accelerator Center offers summer programs where teenagers can work with particle physicists. The message is clear: the next breakthrough might come from a bedroom, not a billion-dollar facility.

If your child expresses interest in nuclear physics, don’t panic, but do pay attention. Jackson’s parents, Chris and Jill Oswalt, supported their son while ensuring safety remained paramount.

They invested in proper radiation detection equipment, consulted with physics professors, and maintained open communication with local authorities. They transformed their home into a learning laboratory while keeping risks manageable.

Most importantly, they didn’t dismiss Jackson’s ambitions as impossible. In an era of climate crisis, young people desperately want to contribute to solutions. Nuclear fusion represents hope, a way to power civilization without destroying the planet.

Jackson’s achievement forces us to confront difficult questions about our energy future:

If a 12-year-old can achieve fusion, why are we still burning fossil fuels? The answer involves more than technology, it’s about entrenched interests, infrastructure investments, and political will.

Why do we accept energy scarcity when fusion fuel is virtually limitless? Deuterium from seawater could power humanity for millions of years. The barrier isn’t resources, it’s technology and implementation.

Are we artificially limiting fusion development by concentrating resources in massive projects? Jackson’s success suggests that distributed research, thousands of small experiments rather than a few giant ones, might accelerate breakthroughs.

Jackson Oswalt, now in college studying nuclear engineering, continues pushing fusion boundaries. He speaks at conferences, mentors other young scientists, and works on making fusion more accessible.

His message resonates with a generation facing climate catastrophe: “Stop waiting for someone else to solve the problem. The tools exist. The knowledge is available. What’s missing is people willing to try.”

This philosophy extends beyond fusion. Whether it’s renewable energy innovation, carbon capture technology, or sustainable agriculture, young people are refusing to wait for institutional solutions.

As COP conferences produce more promises than progress, as fossil fuel companies post record profits while the planet burns, Jackson’s story offers something precious: proof that transformative change can come from unexpected places.

The fusion reactor in his bedroom wasn’t just a science project. It was a declaration that the future of energy won’t be determined solely by governments and corporations. It will be shaped by anyone brave enough to challenge the impossible.

When federal agents left the Oswalt home that day, they reported no radiation danger. What they couldn’t report was the more profound truth: they had witnessed the beginning of an energy revolution that no government can control, no corporation can monopolize, and no force can stop.

The future of clean energy might just be building a fusion reactor in their bedroom right now. And this time, the FBI probably won’t be the only ones paying attention.